The West End Hotel and Land Company of Winston held its organizational meeting on May 29, 1890 to plan “the erection of a hotel, first class in all its appointments and with every modern improvement–one of the institutions we most need.” The company elected William A. Whitaker, a tobacco manufacturer, as president, and the directors included some of Winston’s and North Carolina’s greatest industrialists such as R.J. Reynolds (tobacco), P.H. Hanes (tobacco), James A. Gray (Wachovia Bank), and J.W. Fries (Fries Manufacturing and Power). The company represented “paid up capital of $300,000” and on July 2, 1890 it purchased approximately 180 acres northwest of Winston from Henry J. Fries for $134,142.40. The land had belonged to Johann Christian Wilhelm Fries, Henry’s father and J. W. Fries’ grandfather.

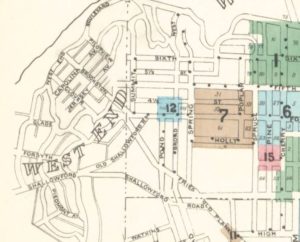

- Map of land holdings before neighborhood was created: Plat 8, Page 66

- Original advertising West End Hotel and Land company PDF

By August, 1890, Jacob Lott Ludlow, a resident of Summit Street in the West End area and Winston’s first city engineer, had laid out the curving streets of the West End Hotel and Land Company’s resort and residential development in sharp contrast to the grid plan of earlier years. Section-1 of the development included the area known today as “Crystal Towers” while Section-2 included the area around the hotel site and what is known today as “West End South.”

Jacob Lott Ludlow was a native of Spring Lake, New Jersey, who received both his Bachelors (1885) and Masters Degrees (1890) in civil engineering from Lafayette College in Easton Pennsylvania. After an extensive prospecting tour throughout the West and South, Ludlow arrived in North Carolina in 1886, and established a general engineering practice in Winston. In 1887 Ludlow built his house (107) on the SW comer of Fifth and Summit Streets in the fashionable western section of the city. He established himself as a consulting civil engineer in municipal, sanitary and hydraulic problems, and he was called upon in an advisory capacity or to design and supervise water supply and sewerage systems in a number of towns and cities in the South. From February 1889 until February 1892 he served as Winston’s first city engineer and worked toward establishing a comprehensive sewerage system and paving the streets.

In 1890, during his tenure as city engineer, Ludlow received his Master’s degree in civil engineering from Lafayette College. It may certainly be speculated that while he was taking this course of study in the northeast he became familiar with the work of Frederick Law Olmstead and when asked in 1890 to design the development of the West End Hotel and Land Company he did so using the picturesque concept of suburban planning promoted by Olmstead. Ludlow sited the Zinzendorf Hotel to take advantage of one of the highest elevations in the city, and he also laid out residential lots on the surrounding hills along curvilinear streets and boulevards which suited the topography and created a visually idyllic setting interspersed with parks. “Little Louise Park” was planned NE of West End Boulevard’s intersection with Spring Street in Section-1 and was named for Ludlow’s daughter, Louise. Grace Court (161) was designed in front of the Zinzendorf Hotel and named for Grace Whitaker, daughter of William A. Whitaker, president of the West End Hotel and Land Company, and Springs Park (80) was situated in the ravine between West End Boulevard and present-day Broad Street.

The street pattern of the West End development was executed according to plan except for the deletion of Fries-Dun Circle between Summit Street (now Manly) and West End Boulevard, and Park Avenue, which appears to have followed closely the path of Broad Street today. In Ludlow’s plan West End Boulevard meandered from Spruce Street on the east to circle around Piedmont Avenue on the south. Part of the original West End Boulevard has been renamed Fourth Street. The only rectilinear blocks in the entire area are the two blocks bounded by Jersey, Carolina, Clover and Pilot View Streets.

The importance of Ludlow’s plan and the West End’s development was graphically illustrated  when the 1891 Birds-Eye View Map of the Twin Cites Winston-Salem featured the West End in its foreground, in sharp contrast to the rectilinear block patterns of Winston and Salem. Even more emphasis was placed on the Zinzendorf Hotel’s importance since it was shown prominently in the central foreground of the 1891 map, even though it would not be completed until May, 1892.

when the 1891 Birds-Eye View Map of the Twin Cites Winston-Salem featured the West End in its foreground, in sharp contrast to the rectilinear block patterns of Winston and Salem. Even more emphasis was placed on the Zinzendorf Hotel’s importance since it was shown prominently in the central foreground of the 1891 map, even though it would not be completed until May, 1892.

The groundbreaking for the Hotel Zinzendorf took place in April, 1891, but the hotel did not open for business until May 9, 1892. The Richmond and Danville Railroad began selling summer resort excursion tickets to Winston, and by May 26 the streetcar line had been extended to the hotel. The local Union Republican extolled the Zinzendorf in a May 26 front-page article which read: “It is situated 1100 feet above sea–on a hill from which the land seems to flow down to the valleys which lie around it… on the warmest days it is fanned by whatever breeze may move the leaves. It is surrounded by porches 18 feet wide keeping always a most grateful shade… It has elevators, electric lights, hot and cold public and private baths on every floor. Electric bells, most approved fire escapes and apparatus… The waters, the air, and charming scenes are all at Winston-Salem. The delightful creature comforts are at THE ZINZENDORF.”

The groundbreaking for the Hotel Zinzendorf took place in April, 1891, but the hotel did not open for business until May 9, 1892. The Richmond and Danville Railroad began selling summer resort excursion tickets to Winston, and by May 26 the streetcar line had been extended to the hotel. The local Union Republican extolled the Zinzendorf in a May 26 front-page article which read: “It is situated 1100 feet above sea–on a hill from which the land seems to flow down to the valleys which lie around it… on the warmest days it is fanned by whatever breeze may move the leaves. It is surrounded by porches 18 feet wide keeping always a most grateful shade… It has elevators, electric lights, hot and cold public and private baths on every floor. Electric bells, most approved fire escapes and apparatus… The waters, the air, and charming scenes are all at Winston-Salem. The delightful creature comforts are at THE ZINZENDORF.”

1892 was a successful summer at the Zinzendorf, but the fall brought disaster. Headlines in the Salem People’s Press on December 1, 1892 read: “FIRE! FIRE! The Beautiful Hotel Zinzendorf Utterly Destroyed.” The fire began on the western side of the building in the boiler and laundry rooms and quickly spread to the dining hall; it was fanned by a northerly wind. Everyone escaped injury, but the large crowd which had gathered to watch the flames was driven back to Summit Street because of the intense heat generated by the wood-shingled structure. Fire engines from Winston and Salem sped to the conflagration only to discover that there was no water with which to combat the flames. Within an hour, the hotel was a smoldering ruin and Winston’s dream of becoming a resort community went with it.

Even before the Zinzendorf Hotel disaster the West End Hotel and Land Company had sold some of the residential lots laid out by Ludlow, but after the fire the development became exclusively residential. Fourth and Fifth Streets west of the commercial area and Summit and Broad Streets already featured the commodious houses of prominent citizens including Robert Glenn (NC governor, 1905-1907) and R.J. Reynolds, and the streetcar had been extended along Fourth Street to its western terminus at the Zinzendorf Hotel, just outside the eastern boundary of the new West End development. Clustered around the comer of Summit and Fifth Streets, were the houses of J.L. Ludlow (107), R.E. Dalton (105), B.J. Sheppard (106), and Jacquelin P. Taylor (74). Ludlow’s house was built in 1887 by Fogle Brothers Lumber Company, a prominent local construction firm. It is a frame, late Victorian house of Queen Anne style influence, R.E. Dalton, a local tobacco manufacturer, built his substantial brick late Victorian dwelling in 1890. It, too, was constructed by Fogle Brothers. In 1892 B.J. Sheppard (106), a leaf dealer and later a veneer manufacturer, purchased his lot next to Ludlow’s and built his brick, eclectic structure shortly thereafter. It is one of the most unusual houses in the city with its parapeted roofline and finials.

Even before the Zinzendorf Hotel disaster the West End Hotel and Land Company had sold some of the residential lots laid out by Ludlow, but after the fire the development became exclusively residential. Fourth and Fifth Streets west of the commercial area and Summit and Broad Streets already featured the commodious houses of prominent citizens including Robert Glenn (NC governor, 1905-1907) and R.J. Reynolds, and the streetcar had been extended along Fourth Street to its western terminus at the Zinzendorf Hotel, just outside the eastern boundary of the new West End development. Clustered around the comer of Summit and Fifth Streets, were the houses of J.L. Ludlow (107), R.E. Dalton (105), B.J. Sheppard (106), and Jacquelin P. Taylor (74). Ludlow’s house was built in 1887 by Fogle Brothers Lumber Company, a prominent local construction firm. It is a frame, late Victorian house of Queen Anne style influence, R.E. Dalton, a local tobacco manufacturer, built his substantial brick late Victorian dwelling in 1890. It, too, was constructed by Fogle Brothers. In 1892 B.J. Sheppard (106), a leaf dealer and later a veneer manufacturer, purchased his lot next to Ludlow’s and built his brick, eclectic structure shortly thereafter. It is one of the most unusual houses in the city with its parapeted roofline and finials.

The West End Hotel and Land Company’s residential development was a logical extension of this fashionable part of Winston leading West from Broad Street. In fact, an extension of Summit Street was included in the new West End development. One of the earliest residents in the new West End development area was Edgar Vaughn, a prosperous grocer who purchased his lot at the corner of Forsyth and West End Boulevard (now Fourth Street) (371) from the West End Hotel and Land Company in July, 1892, and built a frame Queen Anne style residence. Vaughn paid $1620 for the lot and his deed and others like it stipulated that “the said grantee… shall not within five years from the date hereof erect… on the said land… any building or buildings actually costless separately than the sum of $1000 (necessary outbuildings… excepted).” The restrictions outlined in Edgar Vaughn’s deed were not unusual for late nineteenth century streetcar suburbs in North Carolina, or in other states, for that matter.

The suburban ideal, as it developed in America after the mid-nineteenth century, was based on social status, wealth and a desire to return to nature away from the unpleasant aspects of the industry and commerce of the center city. The streetcar as a mode of transportation (and later the automobile) made it possible for people to live further away from their places of work and to live in idyllic settings which still gave access to their factories and other commercial pursuits. The major characteristics of these early suburbs, as promoted on the national level by Alexander Jackson Davis, Frederic Law Olmstead, and others, included picturesque natural settings, parks, social and economic homogeneity, diverse house styles, and modern improvements such as streetcar lines, electric lights, and water and sewer systems.

While suburban developments and streetcar suburbs were a common theme in North Carolina’s towns and cities during the late nineteenth century, the West End was one of the earliest of these developments and it was the first picturesque suburb in the state to be developed according to its original design.

- The Montford neighborhood in Asheville is similar to the West End, but the original developer (Asheville Loan Construction and Improvement Company), was not successful in developing the original (undated) plan by Nier & Hartford Engineers of Chatanooga, TN. In 1894 the Montford area was sold to George Pack, a prominent Asheville developer, who used the plan in a modified way.

- Fisher Park, a streetcar suburb in Greensboro was promoted as early as 1889, but it was not developed from a picturesque suburban plan – its streets were laid out in a grid pattern. In 1901, however, the developer Basil Fisher further promoted the area by donating a tract of land as a city park to create a more idyllic setting.

- Charlotte’s first streetcar suburb, Dilworth, began selling lots in 1891, and it also featured a grid arrangement of streets with a park in the center and a wide boulevard near the perimeter. Many of these early streetcar suburbs, including the West End, continued to thrive and develop into the era of the automobile.

By 1899 most of the lots in the West End Hotel and Land Company’s development had been sold and the Company was trying to “wind up its affairs and discontinue business.” On May 1, 1899, attorney J.C. Buxton, representing the West End Hotel and Land Company, appeared before the Winston Board of Aldermen and requested the city “to take the necessary steps to adopt the streets within the corporate limits that had been built and kept up at the expense of the Company heretofore.” He stated that the company would furnish the gravel to place all the streets in good condition.

Many of the lots in the West End development were purchased as speculative investments, and residential development before 1900 was sporadically placed around Section-1 (now behind Crystal Towers) and in the area of West End Boulevard (now Fourth Street). While it is unclear exactly when the West End development was officially absorbed into Winston’s town limits, it was probably around 1900 since construction in the neighborhood soared after that year and by 1909 the city was paving Fourth Street in the area. Around the time of the consolidation of Winston and Salem in 1913 an extensive paving program was undertaken which included the West End area.

National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination (1987)