The West End is one of the most fully-realized and intact examples of a “turn of the century” streetcar suburb in North Carolina, retaining to a remarkable degree the integrity of its primary period of significance, 1887-1930. The late nineteenth-early twentieth century urban neighborhood is defined by its picturesque landscape features, including a system of curvilinear streets, terraced lawns with stone retaining walls and steps, and parks, which take full advantage of the dramatic hilly topography of the site, and by its rich and varied collection of architecture reflective of the West End’s period of development.

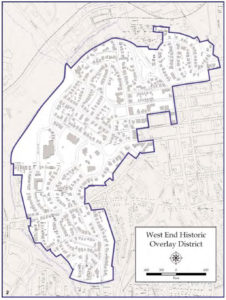

Originally situated on the western edge of the town of Winston, the continued Westward growth of the city has left the district a center-city neighborhood on the western edge of Winston-Salem’s central business area. The crescent-shaped district is bounded roughly by West End Boulevard (NE and north), Peter’s Creek through Hanes Park (NW and W), Sunset Drive (W and SW), West End Boulevard and Interstate-40 (S), and W. Fourth Street (SE and E) meandering in a NEdirection back to Fifth Street, Broad Street, Sixth Street, and to the junction of West End Boulevard, Chatham Road and Buxton Street (NE corner). The boundaries include that part of the original West End development which retains its integrity, as well as small areas of associated property along some of the original borders.

Originally situated on the western edge of the town of Winston, the continued Westward growth of the city has left the district a center-city neighborhood on the western edge of Winston-Salem’s central business area. The crescent-shaped district is bounded roughly by West End Boulevard (NE and north), Peter’s Creek through Hanes Park (NW and W), Sunset Drive (W and SW), West End Boulevard and Interstate-40 (S), and W. Fourth Street (SE and E) meandering in a NEdirection back to Fifth Street, Broad Street, Sixth Street, and to the junction of West End Boulevard, Chatham Road and Buxton Street (NE corner). The boundaries include that part of the original West End development which retains its integrity, as well as small areas of associated property along some of the original borders.

While all was originally known as the “West End“, the area today includes what is commonly called the West End, West End South (South of First Street), and Crystal Towers (East of Broad Street). Within the district the system of curving and straight streets, which respond to, rather than resist, the topography of the land, establishes a collection of irregularly-shaped blocks. Major streets include West End Boulevard, which winds its way through the district from the NE corner to the SW edge, and Summit Street, Brookstown Avenue, Glade Street, and Fourth Street. The district is composed of forty-six whole or partial blocks with 610 recorded properties and their accompanying outbuildings. While the West End is, and always has been, primarily residential in character, there are some commercial buildings, churches, and miscellaneous structures such as the YWCA and the YMCA.

As an entity distinguished from its surroundings, the West End today remains much as Jacob Lott Ludlow designed it in 1890: a picturesque residential neighborhood which emphasizes the natural qualities of its landscape through the use of curving streets and occasional parks. Into this idyllic setting were built some of the finest houses in Winston-Salem between 1887 and 1930, representing the most popular architectural styles of the day, along with a collection of less sophisticated yet well-built and representative examples of the same styles. Other man-made components of the district include numerous outbuildings associated with the houses, four architecturally significant churches, several commercial buildings and apartment buildings from the West End’s primary period of development, and post-1930 structures including a variety of houses, apartments, and commercial buildings along with the YWCA, the YMCA, and an arrowhead-shaped granite memorial marker to Daniel Boone (610). In addition to its distinctive plan and architecture, the West End is definable from its surroundings due to noticeable changes in land use and building type beyond its boundaries, such as more recent commercial buildings and parking lots to the east and southeast, later and/or lesser quality housing to the southeast, an interstate highway (I-40) along the south and SW, later schools and park land to the west and northwest, and small-scale commercial and industrial development to the north.

Of central importance to the character of the West End is its landscape plan as designed by Jacob Lott Ludlow, Winston’s first city engineer. Influenced by the picturesque concept of suburban planning as promoted on the national level by Frederick Law Olmstead, the West End plan, which remains largely intact today, takes advantage of the dramatic topography of the area. Curving streets, with West End Boulevard a prime example, meander through the neighborhood along with some straight streets, creating an assortment of irregularly-shaped blocks. Physical remains around the intersection of Brookstown Avenue and Fourth Street reveal that at least some of the streets were paved with granite blocks, but all are now covered with asphalt. To provide convenience for houses located on steeply sloping lots, many of the blocks are divided lengthwise by narrow, unpaved, service alleys. West of the Summit Street ridge, the land generally slopes downward from East to West and the lots are frequently terraced to accommodate the changes in elevation. In a sense the street system itself is terraced, with, for example, Jersey Avenue, Carolina Avenue, and West End Boulevard aligned in descending order from Summit Street, with Pilot View Street, Brookstown Avenue, and Clover Street intersecting in a steeply downhill direction and terminating at low-lying Hanes Park in the Peters Creek flood plain. This terraced arrangement of streets is repeated south of Glade Street, with Piedmont Avenue, West End Boulevard and Sunset Dr. in descending order from Fourth Street and in this case intersected by the steeply sloping Forsyth, First, and Jarvis Streets.

National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination, Section-7 (1987)